NextDecade (NEXT) is a pre-revenue, Houston-based U.S. LNG (liquefied natural gas) export company, aiming for first shipment by late 2027. After the U.S. began producing more shale oil and gas from fracking, an LNG terminal export race began in the early 2010s. NEXT was formed in pursuit of running this race.

A Bet on Brownsville

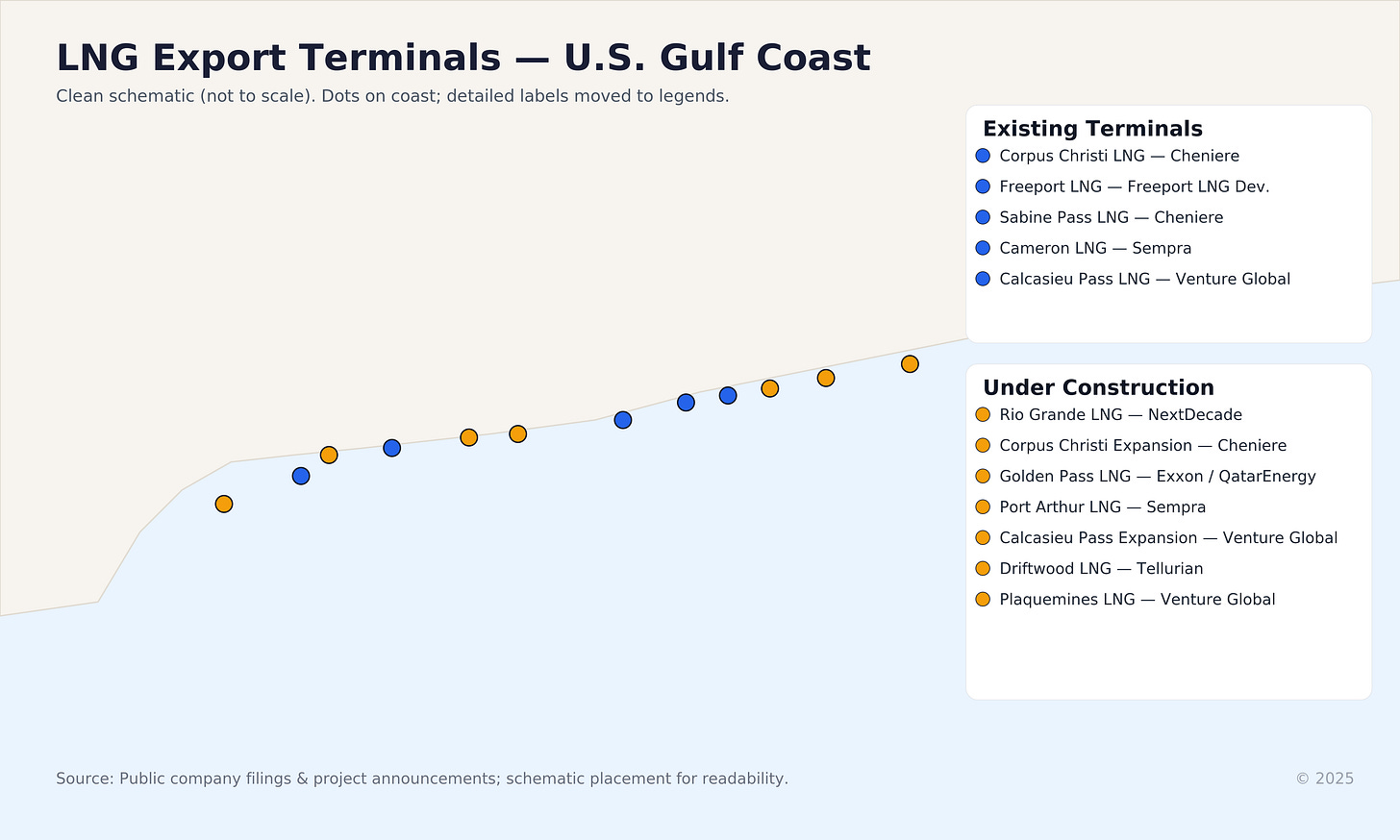

They own and operate their flagship Rio Grande LNG project in Brownsville, TX, which is currently the first (and only) LNG project that will have CO2 emissions less than 90% via carbon storage. Worth note is there are eight U.S. LNG export terminals, with seven more under construction (and more planned). Port geography is a big factor in the economics and reliability of U.S. LNG export projects.

All export facility geographies have their positives and negatives. The gulf coast has the deepest existing ship channels. Decades of industry traffic translate to a surplus of experienced crew and infrastructure. It is the shortest voyage to the Atlantic, minimizing sail distance to Europe. There are also abundant utilities and pipelines, owing to the nearby Haynesville Shale acreage. The negatives?

These facilities are in the Hurricane corridor.

In contrast, Rio Grande has a far lower hurricane frequency, is virtually uncongested (as there is no existing ship traffic) and has ample room for additional buildout. As its close to the border, the facility could theoretically serve both U.S. and north Mexico markets. The downsides are significant: 2-3 days longer sailing distance to Europe. Due to the remote locale, all supporting infrastructure, port dredging, tugs, utilities, breakwaters, must be built from the ground up. It lies farther from gas fields, requiring a 130-mile pipeline. This all raises cost.

In summation, Rio Grande has the lowest hurricane risk, and the least congestion for facility expansion and ship traffic but is relatively far away from industry hubs. If successful, Rio Grande will take gas from the Eagle Ford and Permian fields to liquify and sell, both domestically and globally. The business is simple. Receive and gather natural gas, liquify it, and charge buyers a premium for this process. The different liquefication installations on the property are commonly referred to as “trains.” My best mental model for it is a gargantuan, highly specialized real estate play serving as a toll booth for U.S. LNG exports. Just like big ticket real estate, huge quantities of debt are needed.

‘Wild West’ LNG Markets & Rio Grande’s Trains

The LNG business works like this: plant owners enter largely long-term, fixed contracts with customers — big energy firms — to sell them gas at fixed prices once construction is complete. Since these are long-term contracts, contractual fine print is key. This long lead time was recently used creatively by Venture Global (VG) and has since become the source of a massive lawsuit from disgruntled partners. Basically, VG kept pieces of their projects under “construction,” while already having completed facilities for other sales (other than their lock-in contracts). LNG prices have been quite volatile, driven by things like Covid-and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and many contracts were struck at low price. Now price is high, temptation for cheating is large. Because the long-term contracts only require delivery once construction was complete, VG technically didn’t have to deliver. But they are producing lots of gas that they can sell on the market at much higher prices. So, they did. Now, they are getting sued. The global energy market is a wild west of sorts. There is no central clearinghouse or authority enforcing any rulebook. Every deal is complicated by ever-political bilateral negotiations.

When an initial partnership is consummated (prior to finished construction), these long-term contracts become SPA’s (Sales and Purchase Agreements). The SPAs dictate how much, how long, and what type of delivery. NEXT has SPAs for the first 5 trains, with around 75% of capacity, at an average length of ~19.2 years. Once SPAs are secured, firms get construction financing. As these are enormously expensive projects, with each train costing billions of dollars, SPAs are key to financing. Financing for Rio Grande’s Phase 1 largely comes from Global Infrastructure, TotalEnergies, GIC, and Mubadala. This leaves NEXT with an interest of just over 20% in the first three trains.

Including contracted buyers, as well as development partners, NEXT has contracts with ExxonMobil, Shell, ADNOC, Saudi Aramco, TotalEnergies, ConocoPhillips and Bechtel. Right now, Global Infrastructure Partners, GIC and Mubadala are on the hook for 50% of the capital for Trains 4 and 5, while Total is responsible for the remaining 10%. This leaves 40% to NEXT.

Spearheaded by Bechtel, a world-renowned LNG contractor, Phase 1 construction at Rio Grande broke ground in 2023. Train 1 completion is expected late 2027, with two and three coming in 2028/29. This will complete “Phase 1.” Upon completion, there will be 17.6 million tons per annum (MTPA) of export capacity. Final investment decisions have been completed for Phase 2 (Trains 4 and 5). If Phase 2 is a success, export capacity would jump to of 27 MTPA.

So, how do the numbers play out?

Phase 1 is the first three trains. Upon completion, NEXT will own about 20% of the equity. Contracted fixed fees for Phase 1 is $1.8 billion annually. The company estimates that, after everything is taken out (interest, maintenance, operation cost), it will receive $200-300m of cash flow annually. However, let’s not take them at their word. Let’s say it ends up half that expected windfall, so $100-150m per year of cash flow. NEXT has stated that they will use the cash flow from Phase 1 to deleverage. That said, the cash can be used for buybacks, dividends, or any other venture or investment leadership sees fit as well. Even if we use the middle number of our lowered estimate, $125m, that’s a huge amount of free cash flow for a company trading at $1.5 billion. My tentative estimate for the completion of the final of the three trains of Phase 1 is early 2029. Train one is supposedly coming online in late 2027.

Free cash flow should then start filling company coffers.

If the First Phase is a success, and they can deliver again, they have the potential for increased equity stakes in the Second Phase beginning in the 2030s. NEXT owns 40% of Train 4. And 50% of Train 5. There are performance incentives to eventually own up to 60% of 4, and 70% of 5. If they can secure 50% or more ownership in trains 4 and 5 without further dilution (while completing construction in a timely manner), it will be a huge win for shareholders. If they can survive and execute on both Phases into the mid-2030s, manage their capital and debt well, and don’t hit the rocks from a black swan or executive mismanagement, Trains 6-8 would be a homerun. It’s a hell of a job, but NEXT has a formidable amount of momentum. Obviously, the dream bull case is that the company will make it to Trains 6-8, which will be majority or wholly owned by NEXT. Each one is projected to generate ~$500 million free cash flow. Cheniere Energy, the premier LNG player in this space, produces ~$2.3 billion of free cash flow annually and has market cap of $40 billion. Cheniere has a price to earnings ratio of 12, which is reasonable given the industry. NEXT currently trades at ~$1.5 billion.

TELL vs. NEXT

Investors often recall Tellurian’s collapse — a cautionary tale in LNG development. The difference is timing and discipline. Tellurian tried to build before securing firm long-term buyer contracts or financing, creating a fatal feedback loop: counterparties walked, costs rose, and bankability vanished. NEXT flipped that playbook — it locked down SPAs and full Phase 1 financing before expansion. Unlike Tellurian, whose Driftwood project failed for lack of bankability, NEXT’s contracts, capital stack, and regulatory footing are already in place.

Legal Challenges

In late 2024, the D.C. Circuit Court temporarily overturned Rio Grande LNG’s FERC permit, halting construction and raising fears of new political headwinds under a Harris Administration. That uncertainty eased in mid-2025 when FERC issued a Final Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement addressing the court’s concerns, restoring the project’s legal standing. NextDecade also holds Department of Energy export authorizations under the Natural Gas Act, which provide a durable legal basis for international sales and cash-flow generation once operations begin.

These approvals materially reduce what was once the project’s biggest overhang. Legal precedent now limits the government’s ability to revoke export permits arbitrarily. When the Biden administration tried to pause new LNG authorizations, a federal judge ruled the move “completely without reason or logic,” reinforcing the strength of existing approvals.

While a future hostile administration could slow permitting, outright shutdown of an active facility is highly improbable. With regulatory clarity largely restored, policy risk has shifted from existential to background noise. A pro-energy administration in 2028 would further accelerate expansion, making this a clear catalyst for re-rating the stock.

Risks

There’s still much risk. With a relatively tiny market cap of ~$1.5b, enormous amounts of debt and partnerships with heavyweights are crucial to getting a seat at the table. If a force majeure shifts dynamics enough, the deep-pocketed, sharp-elbowed partners who currently provide momentum, could turn fatal. Execution risk, like major construction delays, is always there. Delays or cost overruns crush value. Many firms without deep pockets or existing cash flow often go bankrupt or continue to pile on debt and dilute shareholders. LNG demand could drop, although current projections don’t indicate this. I have strong conviction this will not be the case. Financiers could pull out. Buyers may not be able to fulfill their SPAs. Russia could flood the European market with natural gas if the war in Ukraine ends. Although, I don’t view this as a likely outcome either. Just recently, E.U. energy ministers met in Luxembourg to begin to hammer out a long-term legal framework to ban purchases of Russian gas. That said, there are other reasons to be wary. In October, CFO Brent Wahl, who had served since 2021, announced he was stepping down to join a digital infrastructure company. NEXT is currently searching for permanent successor. While I don’t love to see this at any company, it’s not a definitively bearish datapoint. It’s certainly worth noting though, especially if we see additional executive departures or insider selling. The bear case is simple: execution stalls, financing dries up, or LNG prices fall before cash flow arrives. Pre-revenue firms die slowly — until they die fast.

A Bullish Case: War Footing and Insider Confidence

Trump’s agenda bodes well for LNG exports. Rising geopolitical tension, rising energy needs and U.S. LNG’s cost advantages underpin a compelling long-term thesis. Global LNG demand will continue to increase materially, especially from Asia and Europe. Europe, who have a limited domestic supply, is turning away from Russian gas. They will likely turn to America. Let’s discuss company leadership. The CEO is Matt Schatzman, who took the job in 2018 and became Chairman of the Board in 2019. Owning roughly ~4% of shares, Schatzman is set for a dynastic sized fortune if he delivers.

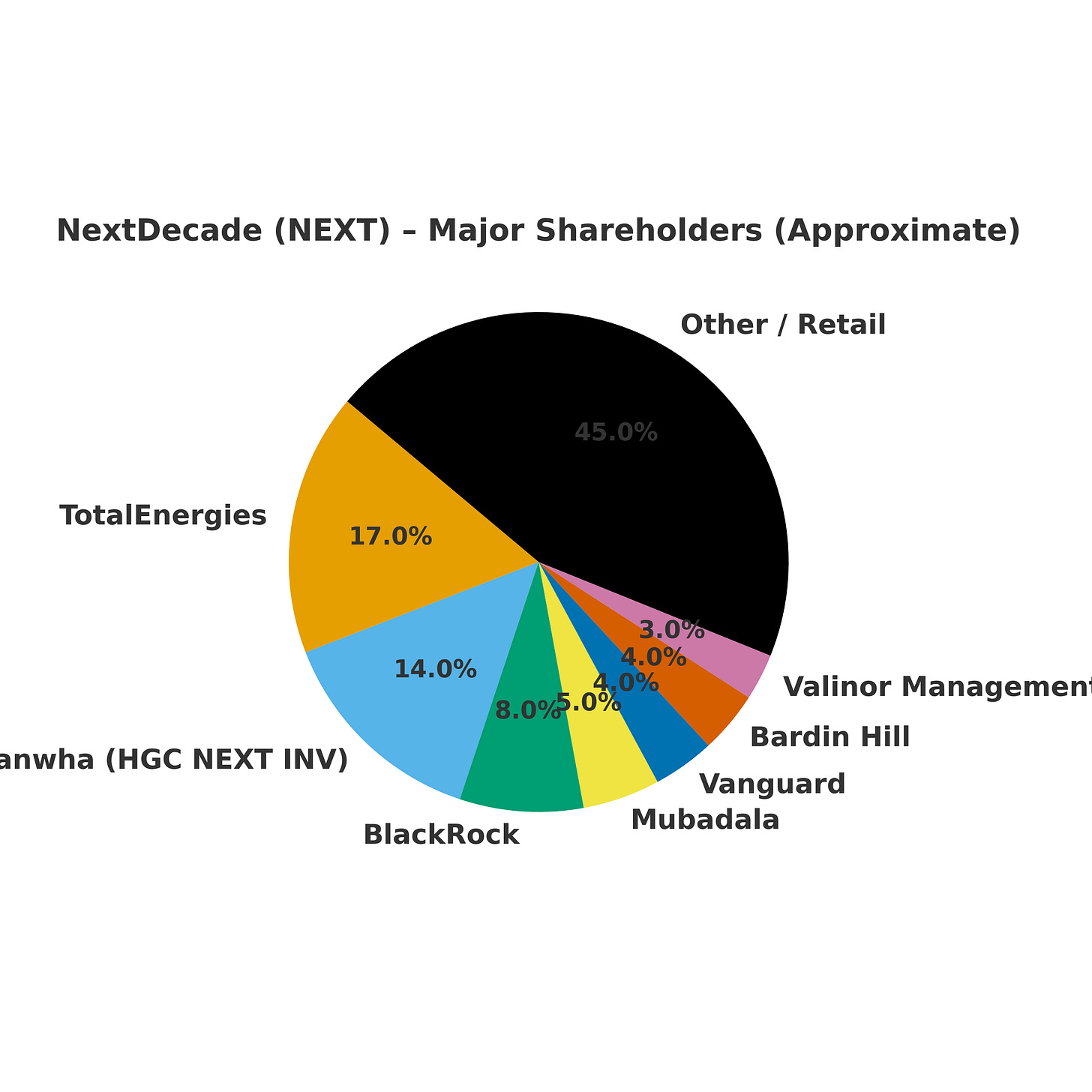

As the share price has declined significantly in the past few months, many insiders have purchased, on the open market, common stock. The CEO bought ~$2 million in shares on September 12th as did William Vrattos (a Lead Independent Director), who bought close to $700,000 five days later. On the 16th, Bardin Hill Investments, which is a private credit markets and event driven strategies firm, bought just shy of $2.5 million. Below is a rough estimate of the stakeholder pie chart.

On the 24th, Hanwha Aerospace bought about $7 million worth of shares. They now own north of 13% of the company. Chaebol-owned Hanwha is quite interesting. Like Samsung, Hyundai and LG, Hanwha is controlled by “chaebol,” which refers to the dynastic, family-owners of the conglomerates that dominate the South Korean economy. Hanwha is one of them. The firm is vital to South Korea as it is the only gas-turbine engine manufacturer for aircraft; also making aerospace parts, armored vehicles, missiles and space/launch vehicles. It’s a conglomerate owning Korea’s most important and vital military components, among a broad range of other assets, including maritime businesses.

Because domestic supply is very limited, South Korea is the world’s third-largest LNG importer. Hanwha’s investment is notable for a few reasons. First, it’s indicative of enormous global demand for U.S. LNG exports. Secondly, LNG could quickly turn into a national security industry if military conflict erupts in the Pacific Theatre. A “war footing” would materially alter the landscape. Energy exports — especially LNG — could be viewed as part of national security infrastructure, not merely commercial. Massive federal spending on logistics, shipbuilding and port infrastructure would get defense-priority guarantees. Quicker expansion, priority access to steel, equipment, and labor. Reduced permitting friction. Increased military or wartime manufacturing would almost certainly increase global demand. Steel, foundry, shipbuilding, aerospace, and chemicals production — all major consumers of high-temperature energy. LNG accounts for roughly 25–30% of total South Korean electricity generation, and a large share of industrial thermal energy (steel, petrochemicals, shipbuilding). Korean heavy industry (POSCO, Hyundai Heavy, Hanwha Ocean, etc.) often run on LNG-fired boilers.

On a war footing, Washington would likely prioritize LNG to friendly nations, potentially using export contracts as leverage. Demand for long-term U.S. LNG supply contracts would likely surge (as seen post-Russia’s invasion of Ukraine). It would almost certainly accelerate and entrench LNG export dominance, at least for the medium term. South Korea, which is a U.S. proxy militarily, is as close to the tip of the spear of any Western ally not named Taiwan or Japan. It makes Hanwha’s stock purchases even more intriguing.

The Bottom Line

This is a bet on LNG assets in their infancy. The nature of NEXT’s position as a small company is to be constantly surrounded by deep pocketed heavyweights. They are in a precarious spot, but if they survive and execute, they will be sitting at a very lucrative table. And they have quite a bit of momentum. It has a complex legal structure, high levels of leverage and gargantuan joint-partner projects with long-term, fixed price contracts. It’s a “hairy” stock. The narrative is not clean. In the short term, markets tend to punish complexity. They reward simplicity. To simplify and strengthen the story, NEXT must deliver on revenue in late 2027, complete Phase 1 by 2029, and hit the ground running for Phase 2 as we enter the 2030s. All while managing its financing, partnerships, staying competitive on cost and avoiding excessive dilution. If the first Two Phases are a success, any additional trains would turn Rio Grande into a national heavyweight. This would likely occur in mid to late 2030s. While it is a major risk that they currently produce no revenue, the confluence of real project de-risking, visible commercial agreements, and unusually large insider buying creates a scenario where the stock could materially reprice in the years to come. If NEXT executes, it could be the next Cheniere — if it doesn’t, it could be the next Tellurian.

Great writeup. What caught my attention is how TotalEnrgies seems to be playing both sides here, financing Phase 1 AND having a SPA as a buyer. Smart way to lock in supply while getting a piece of the upside. Their 10% stake in Trains 4 and 5 seems small though compard to the early position. Wonder if they're hedging against execution risk or just prioritizing capital for their own renewable projects elsewere.